Good Copyright Compliance Practices for Web Content Aggregations

Northern Light is in a single business: providing strategic research portals to global, new product, new technology, and innovation driven organizations in many industries. Our strategic research portals have been used for market research, competitive intelligence, product development, and technology research to global enterprises since 1999. Our current strategic research portal client list reads like a who’s who in technology and industry, including leaders in many industries:

- Life sciences

- Financial services

- Telecom

- Information Technology

- Manufacturing

- Agribusiness

- Consumer Products

- Logistics and Distribution

- Corporate Strategy Consulting

- Energy

Overview of the SinglePoint Solution

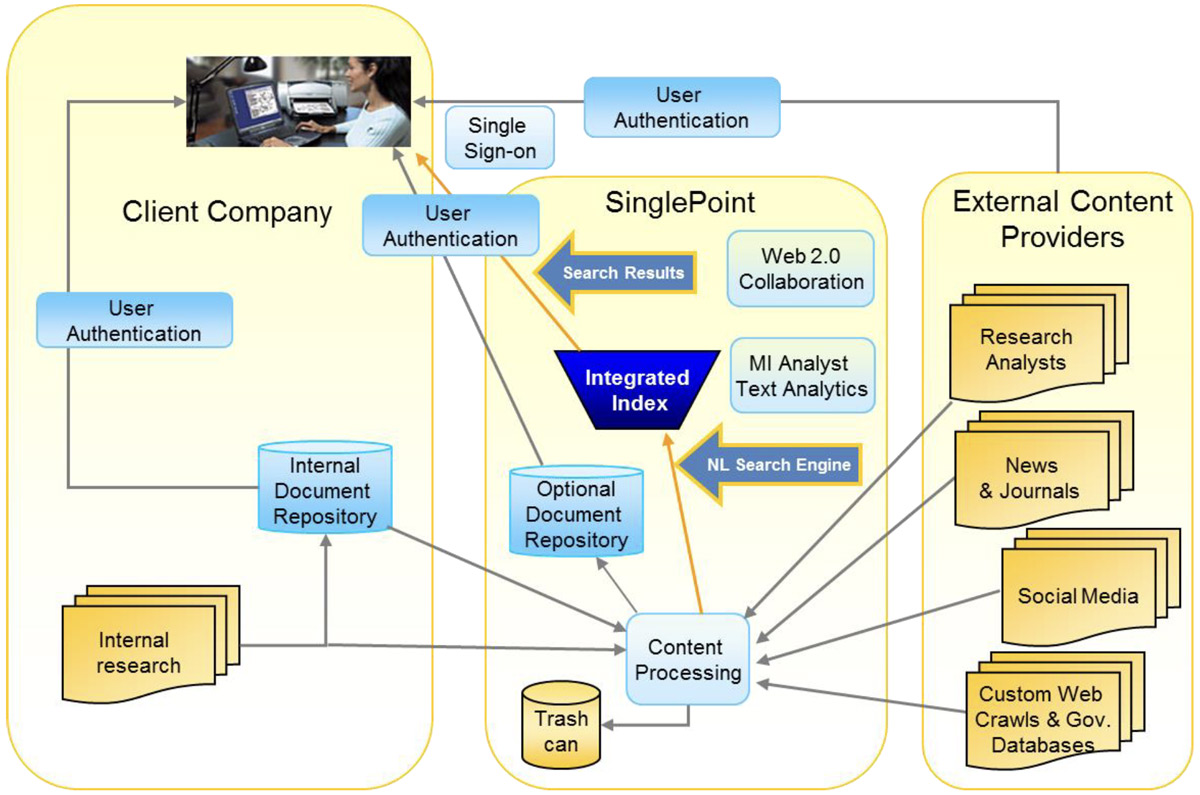

Altogether, there are over 200,000 individual users of our SinglePoint™ strategic research portals at companies like the ones above. SinglePoint is a hosted, turnkey solution provided in its entirety by Northern Light. The client licenses, creates, or simply identifies the content to be included in the research portal, but after that Northern Light handles all other aspects of the portal including development, configuration, deployment, content aggregation, indexing and search, text analysis, collaboration, user management, document security, and reporting. Below is an overview of the SinglePoint solution.

A typical SinglePoint has 10-20 licensed external syndicated research sources with hundreds of thousands of research reports, several internal primary research repositories, a business news feed, and is used by 5,000 users within our client’s organization. Northern Light also harvests content from five thousand websites accounting for 20 million news stories, and indexes 30 million scientific and journal articles.

Northern Light SinglePoint portals enjoy a high ROI, paying for themselves ten to twenty times per year. Northern Light publishes a whitepaper on this topic titled SinglePoint Strategic Research Portal ROI Analysis and it is available in the Knowledge Center on our corporate website at https://northernlight.com/knowledge-center.

Northern Light Experience With Web Content Aggregations

As part of the SinglePoint portal product line, Northern Light provides search and access to several aggregations of Web content to clients. These include:

- Northern Light Business News – 40,000 news stories per day from 5,000 business and technology-focused sources, with 15 million articles in the archive.

- IT Analyst Blogs and IT Analyst Tweets – over 1.5 million posts from 2,300 IT analyst tracked by name through the social Web.

- Life Sciences Conference Abstracts and Posters – over 1.0 million abstracts and posters from over 1,500 research conferences and meetings held around the world since 2010.

- Government News and Publications – 30,000 documents a day representing every news story, announcement, and official document published by over 200 branches, agencies, and departments of the U.S. Government.

Web Content and Copyright

Web content is unruly, misbehaved, messy, scattered, badly formatted, when formatted at all. It’s also informative, insightful, timely, and crucial for business and technical research and analysis.

Web content that is “free” and “openly-accessible” to the public is a fast growing content category that often has the best and most current strategic information. Web news aggregations are now more comprehensive and useful than most licensed newswires. This trend is spreading like an out-of-control wildfire to other content categories including competitive intelligence, social media, scientific research, and regulatory and compliance information.

Copyright infringement can carry substantial financial penalties for companies that distribute or use copyrighted content improperly. However, this issue is of special concern with Web content because, despite being easily accessible without payment of a subscription fee, the content found on webpages is almost always copyrighted. Organizations, users, and even some news aggregators frequently confuse “free” and “openly-accessible” with

“copyright-free.”

Real World Example

To illustrate the importance of getting ahead of the copyright issue, consider this example. A global company solicited bids from Web news aggregators to establish a monitoring system of news coverage of their brands. The requirement included making and storing actual images of the news articles for later retrieval. Two web content aggregators, let’s call them A and B, competed for the business.

Aggregator A declined to provide the requirement to store and reproduce the full-text of the Web news articles on the basis of copyright considerations and was dropped from the bidding process. Aggregator B agreed to the requirement regarding storing images of the webpages. The company spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on the solution with Aggregator B.

The night before the solution was to deploy to internal users, someone in the marketing department, perhaps remembering Aggregator A’s original objection to the requirement to store and reproduce the full-text of the aggregated Web news articles, decided to ask the company’s attorneys to sign off on the solution. The legal depart took one look at the new brand tracking system and vetoed its deployment on the spot.

Why? Because, despite the fact that only “free” and “openly-accessible” content was in the solution, the storing and reproduction of the full-text of the aggregated content potentially violated the copyrights of the content owners. The whole solution was abandoned and the substantially-into-six-figures budget for the project completely lost.

How can your company avoid a situation like this one?

Fair Use

As anyone knows who has used a card catalog in a library or read a book review on Amazon, indexing, excerpting, and summarization of other people’s copyrighted content are not new practices. Indexing services are as old as the publishing business. Book reviewers often reveal substantial portions of a plot and reveal the nature of the protagonists’ personalities. Also, general practice in a wide variety of fields is to quote with attribution from copyrighted works without much, if any, fear of getting sued for it.

From a legal viewpoint, the principal of “fair use” governs the legality of indexing, excerpting, and summarization products. Regarding fair use doctrine, courts apply a four-part test to determine if the copied material is fair use or not.

Web Search Engines And Copyright

The largest aggregation and indexing of Web content is done by Web search engines such as Google. A number of courts in different cases have ruled in favor of Web search engines that have been sued by website content owners for copyright infringement. In those cases, they have found that fair use permits Web search engines to provide indexes, citation metadata, tags, and excerpts of copyrighted content.

Supporting this finding, courts have ruled that the provision of a Web-content index supports a transformative purpose which is the ability of users to sift through a large amount of information which practically speaking would be impossible without the search engine indexes. This sifting process is different than any purpose intended for the original content, and hence transformative.

An additional factor supporting the success of the fair use defense by Web search engines has been that providing links to original material on the Web supports the notion that the indexing, excerpting, and summarization of Web content as practiced by Web search engines does not negatively impact the audience for the copyrighted material, and perhaps actually improves it. The question is whether the copied work, in this case the search excerpts reproducing text from the webpages on search results, substitutes for the original content on the webpages. Google News reports a 56% click-through rate which has been cited as evidence the excerpts of copyrighted webpages in Google’s search results are not in fact substitutes.

AP and Meltwater

The Associated Press (AP) recently sued Web news aggregator Meltwater for copyright infringement of freely-accessible Web news content. This case is illustrative because the court reviewed the entire history of Web-content copyright litigation in its decision. Meltwater defended itself by claiming to be a Web search engine and citing the long string of favorable decisions for Web search engines in prior copyright litigation. In a sweeping victory, the court granted summary judgment to AP on its claim that Meltwater had committed copyright infringement, and that its copying was not protected by fair use.

Trying to briefly summarize the high points of the 94-page court decision, the court ruled that Meltwater was not protected by fair use doctrine in part because:

Lessons For Companies Buying Web-based Aggregations

And for Web content aggregated by an external vendor, make sure your content aggregator:

- Provides only indexes, citation metadata, tags, and short excerpts. These activities are traditional fair use by indexing services.

- Provides excerpts that are a small fraction of the original text. These pieces should not be so complete as to substitute for the original document.

- Does not serve copies of copyrighted material from the aggregator’s own repositories rather than connecting you to the original content. Does not specifically target the lede paragraph in news stories for excerpts.

- Demonstrates a click-through rate on the solution above 50%. The aggregator’s reporting system should help you measure that for your organization’s use of the service as well. (For example, Northern Light’s click-through rates are 76% as measured by our portal reporting systems.)

- Does not have search portal application features or documentation that facilitate copying, saving, or distributing the full-text from websites.

- Uses links to the original documents in every use case, promoting the use of the original material. Portal applications should save links when documents are bookmarked, share links when the articles are shared, and post links when articles are posted to collaboration pages. Working with links to the original webpages instead of copies of the content from the webpages is a copyright-compliant means of saving, sharing, and posting.

- Has a policy and practice to exclude content from any source that objects to being included.

- Licenses full-text content with redistribution rights from sources that are deemed to be essential.

Lastly, have your legal department review the solutions that you are considering licensing for copyright compliance. Do this before you license the solution!